Overview

Rocky Knob Park, one of the first five recreation areas developed alongside the Blue Ridge Parkway, stretches from Milepost 167 to Milepost 174 in the Parkway’s Plateau District. One of the largest parks along the Parkway, Rocky Knob serves as the main recreational area for the southern Virginia section of the road and consists of around 4,500 acres of land.[1]

While the park does not have the same array of resources that make other sites popular with tourists, Parkway engineers did take advantage of the local topography to offer wide-sweeping views of the surrounding mountains, which range in elevation from 2842 feet to 3972 feet, and the valleys below them.[2]

Panoramic View from Saddle Overlook, Rocky Knob, October 17, 2014. Image courtesy of Catherine Cranfill.

Rocky Knob is chiefly a place for picnicking and camping.[3] The site offers a campground with 81 campsites for tents and 28 for trailers and RVs, a picnic area with 72 sites, a visitor center, and several comfort stations for those spending a night or more in the park.[4] Visitors may also hike down to Rock Castle Gorge, view the one-hundred-year-old ruins of a once-thriving community there, and spend the night (with a special permit) at a primitive, backcountry campsite on the site of a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp.

There are also three overlooks in Rocky Knob: Saddle Overlook, Rock Castle Gorge Overlook, and Twelve O’Clock Knob Overlook. Additionally, the park contains several trails totaling nearly 15 miles: Rock Castle Gorge Trail (a moderate to strenuous 10.8-mile loop), Picnic Area Loop Trail (an easy one-mile loop), and Black Ridge Trail (a moderate 3-mile loop). At the summit of Rocky Knob stands a three-sided trail shelter built as a stop along the Appalachian Trail.[5] The structure also has the distinction of being the first building constructed along the Parkway.[6]

Timeline of Events

The Pastoral Landscape: Team of Oxen Driven by Old Farmer, October 23, 1936, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/15802/.

- Before 1776: The first European settlers arrive in what is now the Rocky Knob recreation area.[7]

- 1935: Surveys for the park begin. Photographs taken during this process document a largely pastoral landscape.[8]

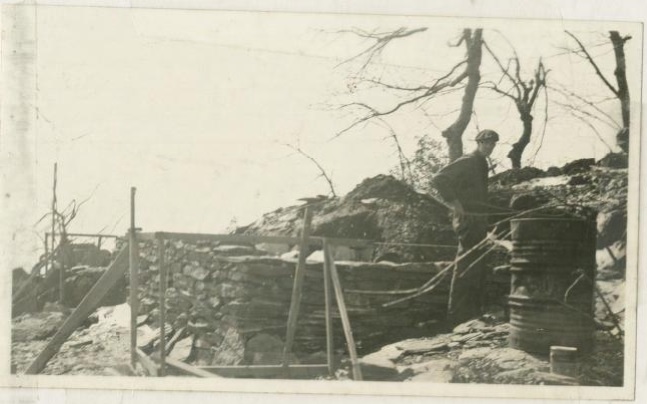

- Mid-1930s: An Emergency Relief Administration (ERA) crew starts construction on a picnic area and a rustic, “Adirondack-style” trail shelter near the summit of Rocky Knob.[9]

Trail shelter under construction, March 1937, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14802/.

- 1936 & 1941: Parkway planners unveil ambitious master plans that call for the addition of a swimming pool, lodge, “Motor Service & Tea Room,” campground, lake, and hiking trails. Only some of these recommended amenities are ever built.[10]

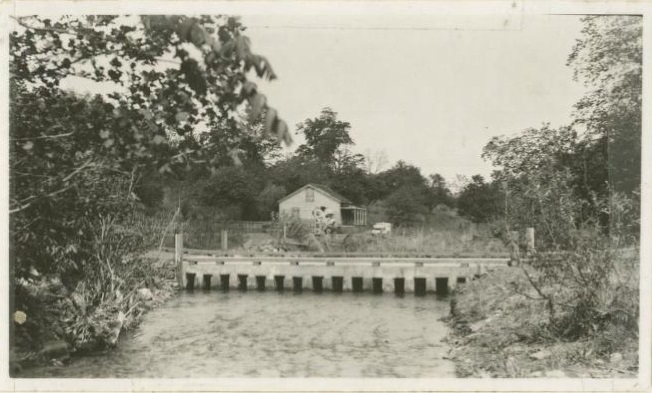

High water ford, Rock Castle Creek at CCC camp site, May 1938, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14801/.

- November 1937: The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a public work relief program created as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, establishes CCC camp NP-14 near Rock Castle Gorge.[11]

- End of 1937: ERA and CCC workers complete construction of the picnic area, trail shelter, and ten miles of trails.

- 1940: The CCC plants several hundred blight-resistant Chinese chestnut trees to replace American chestnuts lost to blight in previous decades. Parkway officials intend to distribute the chestnuts to local farmers, thereby kick-starting the stalled chestnut trade.

- 1940-42: Development of segregated recreation areas for African Americans reaches past the planning stage and into the land acquisition phase, but the NPS drops its segregation policy before any construction begins.[12]

![One of the "trail lodges" under construction, [1941?]](http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/Bldg21-under-construction.jpg)

One of the “trail lodges” under construction, [1941?], Courtesy National Park Service eTIC, Denver, CO, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/MP-174-19-20-21-photo-details-cabins.jpg.

- November 1941: CCC camp NP-14 shuts down.[13] But before the camp’s dissolvement, CCC enrollees construct special “trail lodges” as part of a “Rough-It” camp designed for scouts.[14]

- May 1942: In response to a severe tire rubber shortage during World War II, Virginia places a ban on “pleasure driving,” which forces the Parkway to close the Rocky Knob recreation area.

- August 1943: The state lifts the ban on pleasure driving, and the park reopens, but the site receives few visitors due to continued wartime gasoline and tire rationing.[15]

- September 1945: Designs for a proposed “Rocky Knob Service Center” include a coffee shop and a “Gas & Comfort Station” at the entrance to the picnic area.[16]

Two views of a proposed “Coffee Shop & Gasoline Station” for Rocky Knob, Unknown date, Courtesy National Park Service eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed October 6, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/CoffeeShopandGasolineStationRockyKnob.pdf.

- 1948-September 1949: Parkway officials commission the construction of a gas station.[17]

- 1950: Because the “Rough-It” camp is never used as intended, the NPS converts the cabins into family housekeeping units.

- December 1965: Superintendent James M. Eden briefly considers moving the concessions from Mabry Mill to Rocky Knob to help relieve traffic congestion at the mill, but he drops the plan after the president of National Park Concessions protests.[18]

- 1968: Officials move a “visitor contact kiosk” from the Biltmore area to Rocky Knob to be used as the campground registration kiosk.[19]

- 1978: The gas station undergoes conversion into a visitor center.[20]

Landscape and history

In 1935-1936, Edward Abbuehl, Albert Burns, and Robert Hall came to survey the land that would become Rocky Knob park. These first photographers, surveyors, and landscape architects hired by the National Park Service found a small but persistent community of people and a landscape dotted with farms, mills, and homesteads, all connected by a steep road carved into the mountainside. In the coming months and years, that landscape was transformed by the labor of hundreds of men–many of them put to work under government programs that alleviated the worst impacts of the ongoing Depression. In the years since, the place of these original workers has been taken by many more hundreds of men and women, who interpret and maintain the Parkway that now runs through here and the many campgrounds, trails, and other recreation areas that flank its sides. The effect of all of these changes–from the first surveys, photographs, and reports to the present day–has been to create a landscape that seeks to divide recreation, leisure, and tourism from the working lives and historical landscapes on which the Parkway was built and which persist more than 75 years after its completion.

The following tells pieces of the story of these landscapes: the way that the idea of Rocky Knob has been conceived, designed, built, and maintained as a complex landscape representative of competing desires.

Rock Castle Community to Rocky Knob Park

When Abbuehl and his fellow NPS-hired workers came to the area in 1935 and 1936, they took pictures of the pasture land that they found there. Characteristic is Abbuehl’s photograph from July, 1935 which shows lush, rolling hills with little tree cover and cows grazing in the distance.

Other images taken at the same time, like Abbuehl’s simply-titled documentary shot “View of Rocky Knob, VA,” suggest a landscape significantly altered and in use by local residents.[21] The focus of that photo is the scenic mountain view, but a casual glance at the foreground of the picture shows the outline of a so-called “worm fence,” one undoubtedly constructed to keep roaming cattle away from the steep edge nearby.[22]

Missing in these shots are other signs of the people who owned, lived on, and worked this land. Their presence in the area was quickly coming to an end with the purchase of almost 4,000 acres of land by the Resettlement Administration for Rocky Knob. These purchases ranged in size from the 3.3 acre plot of W.W. DeHart on up through the 436 acres purchased from C.C. Burgess.[23] The process moved swiftly: In just over a year since the initial land surveys, almost an entire community had been purchased and was on its way to becoming a park.

Building Rocky Knob

Once land for Rocky Knob was acquired, its transformation into a park was rapid. Construction, underway by late 1936, often proceeded on a grand scale and at a fast clip as evidenced by photos like these taken at a crusher site in the new park.[24]

By the time a photographer recorded the completed Saddle Parking Area in use just a few months later, the landscape around it had been drastically altered. The visitors depicted in this series of photographs glance out to the valley below, surrounded not by livestock and fences, but by the blacktop of a parking lot designed to accommodate the many thousands of visitors that would stream through this park every year.[25]

But these landscapes of recreation did not entirely supplant the working landscapes that preceded them. Elsewhere in Rocky Knob, just a short drive away and only a few yards off the Parkway, agricultural landscapes persisted long after the Parkway’s completion. Their relationship to the Parkway and to Rocky Knob is complicated: while not a part of either, proximity makes them seem connected. At various times in the history of Rocky Knob, NPS employees have advocated to keep sheep in areas beside the Parkway in order to “maintain the ‘pastoral picture’” of Rocky Knob. The cows currently grazing alongside the road in Rocky Knob are part of a longstanding program of agricultural leases.[26] Sometimes then, the working landscape can seem like a scene of pastoral beauty and heighten the experience for the visitor. But there are other parts of the working landscape at Rocky Knob that cannot be mistaken for beautiful and that are actively hidden from most visitors. These are the sites of work and maintenance, the background to visitor experience at Rocky Knob.

Maintaining Rocky Knob

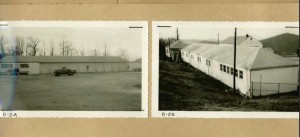

Rocky Knob, like much of the rest the Blue Ridge Parkway, is incomplete. Since its opening, there have been numerous formal expansions to the park. But these large-scale plans for expansion were few and far between. Most building and rebuilding of Rocky Knob occur on a more everyday basis with the continued maintenance of the park and road. Large facilities, like the warehouses, storage buildings, and other equipment depicted in various reports and assessments illustrate a story of an alternative landscape that exists behind the scenes and away from the scenic vistas and dramatic peaks valued by visitors.

Seemingly ordinary photographs from these assessment reports, like that of an incinerator, reveal small details about these ordinary yet crucial operations. The incinerator sketch dates from sometime after its construction in 1941 and includes with it 2 photographs of the piece of equipment at work. The first of these two pictures is particularly evocative: the incinerator, with 55 gallon drums atop, is surrounded by a fence that encloses a large amount of trash waiting to be burned.[27]

The image was clearly taken in winter, just past the prime tourist season, as the spindly trees in the background are free of any leaves. Still, in the distant reaches of the picture, we can see mountain peaks, a reminder of the “natural” or scenic landscape that these structures allow. The photos of the warehouse at Rocky Knob, show even more of the mountain landscape which make this structure seem that much more of an oddity. This massive building, some 160 feet long and constructed of cinder blocks, tin, and concrete, is far different from the calculated rusticity of most Blue Ridge Parkway buildings.[28]

Meant to be used for storage of tools and equipment, this is not a building meant to be seen or appreciated. And yet these buildings and structures are vital to Rocky Knob, holding in them the equipment that allows the park and the parkway to continue serving thousands of visitors each year.

Visitor Experience

Things have altered over the years at Rocky Knob, but it continues to attract visitors to its combination of scenic overlooks and tourist amenities. In many ways, Rocky Knob has both suffered from and been altered by its proximity to the wildly popular Mabry Mill, a site of significant visitor interest that interprets an historic mill and homestead in addition to playing host to a popular restaurant. Rocky Knob, by comparison, holds less interest to the visitor looking for activities. A report from the late 1990s positively interprets this, touting picnic areas that are “rarely crowded” before admitting that “most visitors confine their visits to taking in the marvelous views” from the park’s overlooks.[29]

Rocky Knob then serves as a kind of utilitarian site: a place for visitors to stop briefly on their way to seemingly more exciting attractions or to stay the night at campgrounds that are the only ones available for miles. Indeed, the needs and desires of visitors impacted the site many times in the years since its inception. Around 20 years after the Parkway opened to the public, a new master plan suggested a separation of the picnic and camping areas and a significant expansion of each. The 110-site camping ground opened in 1962 and continues to be well-used by visitors today.[30] In many ways, though, Rocky Knob is a remnant of the past of tourism on the Parkway. With visitors increasingly drawn to attractions like Mabry Mill, or to the proliferation of nearby attractions off the Parkway, Rocky Knob seems likely to continue its prolonged period of gentle inattention. Current issues facing the park, like the resumption of a concessions contract for the rental of its CCC-built cabins, line up neatly with the complicated history of Rocky Knob. Perhaps the one constant in the years since the first National Park Service employees arrived in the area has been a challenge to adapt to change. Often this has been change stemming directly from the Park Service itself and its attempts to transform a place from community to park. The changes now are largely external ones: competition from other tourist sites more attuned to the needs and desires of contemporary visitors. It will be the reaction to these changes that determines the next stage in the history of Rocky Knob.

* * *

Launch Rocky Knob Digital Exhibit

References

[1] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, Between Shenandoah National Park and Great Smoky Mountains, Asheville, Buncombe County, NC, Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540, 1997), 212-17, accessed September 26, 2014, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/nc/nc0400/nc0478/data/nc0478data.pdf.

[2] Ibid., 212; “Current Map of Rocky Knob” (National Park Service, n.d.), accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/blri/upload/rocky-knob.png.

[3] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 217.

[4] “Camping on the Parkway,” Blue Ridge Parkway, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, November 18, 2014, accessed November 28, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/blri/planyourvisit/camping-on-the-blue-ridge-parkway.htm; “Picnicking,” Blue Ridge Parkway, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, November 28, 2014, accessed November 28, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/blri/planyourvisit/picnicking.htm.

[5] “Blue Ridge Parkway :Rocky Knob Trails /” (National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 2000), accessed September 21, 2014, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/pur1.32754073531190; “About the Trail,” Appalachian Trail Conservancy, accessed November 29, 2014, http://www.appalachiantrail.org/about-the-trail.

[6] National Park Service, Visual Character of the Blue Ridge Parkway, Virginia and North Carolina ([Washington, D.C.?]: U.S. Dept. of Interior, National Park Service, 1997), 162-3, accessed November 29, 2014, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015041237267.

[7] National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of Interior, The Saddle, Interpretive Sign, n.d., Rocky Knob Recreation Area, Virginia, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/SaddleOverlookInterpretiveSign.jpg.

[8] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 212; for examples of the pastoral landscape, see Albert S. Burns, Team of Oxen Driven by Old Farmer, Photograph, October 23, 1936, Driving Through Time, accessed September 7, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/15802/; ———, Looking South at Concessions Area, Photograph, August 1936, Driving Through Time, accessed September 4, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14901/. Photos show signs of habitation, such as grazing livestock, fences, and horses.

[9] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 75, 213.

[10] Ibid., 213; F.M.W., “Swimming Pool-Rocky Knob, 1937 :: Blue Ridge Parkway Maps,” 1937, accessed September 21, 2014, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/blueridgem/id/1696; Robert G. Hall and Gilbert Thurlow, “Motor Service & Tea Room, Blue Ridge Parkway at Rocky Knob Park, 1936 :: Blue Ridge Parkway Maps,” 1936, Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway, accessed September 10, 2014, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/blueridgem/id/1725; “Rocky Knob Map, Blue Ridge Parkway Master Plan,” 1941, National Park Service, eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed September 15, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/MasterPlan1941.pdf.

[11] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 76, 213.

[12] Ibid., 213-15.

[13] Ibid., 75-77.

[14] Ibid., 174, 214-17.

[15] Ibid., 80.

[16] “Rocky Knob Service Center :: Blue Ridge Parkway Maps,” Paper (National Park Service, US Dept. of the Interior, September 1945), Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway, accessed December 2, 2014, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/blueridgem/id/626.

[17] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 215-17; Brown & Wells Architects, Gas Station Bldg No. 82, Design, June 6, 1948, National Park Service, eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed September 17, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/GasStationBrownWells.pdf; Charles S. Grossman, Gas Station – Building No. 82, Design, March 15, 1949, National Park Service, eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed September 17, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/GasStationGrossman.pdf.

[18] Ibid., 215-17.

[19] Ibid., 132-33, 216.

[20] Ibid., 217.

[21] Edward H. Abbuehl, View of Mountain Pasture Land, Photograph, July 25, 1935, Driving Through Time, accessed September 4, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14830/.

[22] Edward H. Abbuehl, View of Rocky Knob, VA, Photograph, July 25, 1935, Driving Through Time, accessed September 4, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14892/.

[23] “Map of Lands Acquired for the Blue Ridge Parkway, Recreational Demonstration Project LP-VA-8 Rocky Knob Area :: Blue Ridge Parkway Maps,” December 1936, accessed September 21, 2014, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/blueridgem/id/1683.

[24] R.F.E., Crusher Site and Temporary Roads Outside Site, Photograph, August 13, 1936, Driving Through Time, accessed September 5, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14841/; R.F.E., Damage to Area Adjoining Crusher Site and Truck Parked Outside Site, Photograph, August 13, 1936, Driving Through Time, accessed September 5, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14840/.

[25] Robert G. Hall, Rocky Knob Saddle Parking Area Looking East (Before), Photograph, August 3, 1937, Driving Through Time, accessed September 7, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14858/; Robert G. Hall, Rocky Knob Saddle Parking Area Looking West (Before), Photograph, August 5, 1937, Driving Through Time, accessed September 7, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/14860/.

[26] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 216.

[27] Earl W. Batten, Incinerator, n.d., National Park Service eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed September 14, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/incinerator.jpg.

[28] O.A. Cozzani, Warehouse and Equipment Storage, n.d., National Park Service eTIC, Denver, CO, accessed September 14, 2014, http://blueridgeparks.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8353/2014/12/warehouse.jpg.

[29] Historic American Engineering Survey, Blue Ridge Parkway, 217.

[30] Ibid., 215-17.